How Lonely Sits The City, Part II

(The following is the second essay of a two-part series by Aaron Robertson exploring the history, aesthetics, and appeal of ruins. Read Part One here.)

“Ultimately, all that remained to remind men of the great epochs of history was their monumental architecture…What then remained of the emperors of the Roman Empire? “

— Albert Speer

“The old church was in ruins and the door stood open to the high walled enclosure. When Glanton and his men rode through the crumbling portal four horses stood riderless in the empty compound among the dead fruit trees and grapevines…”

— From Blood Meridian, or the Evening Redness in the West by Cormac McCarthy

“It looks like it has lost a war. It could be Dresden after the Allied bombing. Factories, stores, schools left to rot. Houses gutted by fire. Streets abandoned, derelict, populated by crime.”

— Bob Simon on Detroit

I.

In a lecture entitled “Emerging From the Ruins”, writer and philosopher Marshall Berman recounted a story of the South Bronx in the 1970s. He described instances of city officials blaming the residents (most of whom were either Latino or black) for their own abhorrent conditions, incriminating local Republican politicians for wanting to displace these residents from their homes. “I saw the Bronx in ruins,” Berman said, “and I saw how modern life itself was so full of ruins and the terror of ruins [was] still biblical.”[ref]Marshall Berman. “Emerging From the Ruins.”9th Annual Lewis Mumford Lecture on Urbanism. City College of New York. 2 May 2013. Lecture.[/ref]Berman’s audience waited quietly as he turned to a passage of scripture, Lamentations 1:1, which reads, “How lonely sits the city that was full of people. How like a widow she has become, she who was great among the nations. She, who was a princess among the provinces, has become a slave.”[ref]Lam 1:1. The English Standard Version Bible.[ref]Lam 1:1. The English Standard Version Bible.[/ref] For Berman, the decline of the Bronx was no less momentous than the fall of Babylon, Damascus, and Jerusalem. The spectacle of a city’s implosion, Berman said, was one of the “dreadful primal scenes”. Biblical desolation did not seem so far removed from modern circumstance, and building the bridge between millennia was now as simple as starting a fire.

Berman noticed a resurgence of urban photography fixated on the city’s structural transformation. “Ironically,” he notes, “tearing up the South Bronx created a visual environment that, although horrible, was an amazing spectacle. Heavy artillery and serial bombing have spread spectacles like this around the world.” The South Bronx, then, becomes a victim of sustained aggression and constructional decomposition. Berman believed the events unfolding in the South Bronx indicated the familiar trope of urban dissolution. However, this environment could also serve as a fecund site of aesthetic reinvention. Graffiti artists tagging the sides of trains might transform damaged objects into something refurbished and, perhaps, valuable. Photographers capturing the daily lives of tenets within their lightless apartments could express something that language might not have done as directly.

What could the lens of a camera see that human beings could not? Could literature sufficiently articulate the concept of the ruin, which is historically bound to visual representation? More generally, I wondered, where is the intersection of art and ethics in the context of ruination? This is not the place to expound my own artistic systemology, but I will say this: the artist should be at liberty to frame whatever she wishes. However, I also believe that one of the responsibilities of the socially conscious artist is to consider how their choices might influence the world beyond the canvas or the page. The idea of a “ruin aesthetic” has been resolvable for few, and problematic for many. To believe that such a thing exists seems at once to be an act of fetishization and ennoblement. I am convinced that the ways in which we perceive ruinscapes can have (and have had) tangible consequences, although the nature of these repercussions is contingent on the time in which the particular ruinsite exists. We will see this most clearly in the essay’s final section, which marks my return home, to Detroit. But first, we will backtrack, some seven centuries in the past.

II. The Wife of Lot

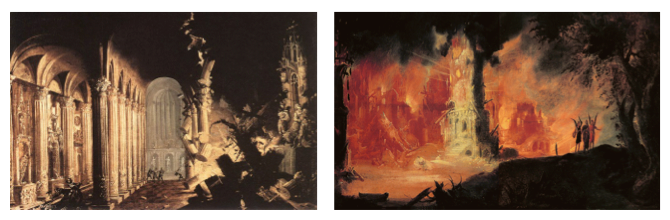

Art historian Paul Zucker proposed three categories to explain how an artist might approach the ruin as a subject. The ruin could be (1) a vehicle of romanticization, (2) a document of the architectural past, or (3) a means of restoring the original spatial organization of the structure. Zucker qualifies his argument by saying that the line between the three categories often blurs, and throughout history these approaches have not always been adequate to convey the creator’s intention. It is not always simple to distinguish between the historical and aesthetic significance of the ruinscape since they had once served as authoritative documents of classical, paganistic cultures (think of Livy’s Camillus, who told the stricken citizens of Rome that the city’s ruins would one day testify to its magnificence). Although ruins were introduced as subjects in Renaissance-era works in the 14th century (often representing the site of Christ’s birth as dilapidated to emphasize his humble origins), it would be another three centuries before they assumed new roles, not as background set pieces, but as the focal point and uniting element of the artist’s vision. Many painters, such as Monsu Desiderio, Michaelangelo Cerquozzi, Salvator Rosa, and Sebastiano Ricci manipulated light and color to depict surrealistic ruins that could have embodied a post-apocalyptic state. Zucker writes, “[T]he appearance of withering destruction fascinates [these artists] more than architectural exactitude.”[ref]Paul Zucker, “Ruins. An Aesthetic Hybrid” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 20 (1961): 120, JSTOR, 6 October 2013[/ref] The relegation of historical accuracy to pseudomythical narration augured the appeal to emotion that would later be associated with Romanticism.

Let us look at some of Monsu Desiderio’s work. After the prophet Azariah implored Asa, King of Judah, to enforce a strict observance of Judaism, Asa extirpated the former religious symbology and places of worship from the land. Desiderio’s King Asa of Juda Destroying the Idols (pictured above on the left) represents the Hebrew King’s purging of non-Judaic idolatry. The painting’s thematic and aesthetic composition emphasizes abrupt transition and unambiguous contrast. The center of the painting shows the building’s apse — the semicircular termination wherein altars and clergymen are usually situated. Three marmoreal sculptures, each of which is athletically well-defined, stand in their niches. The apse and transept — the transverse section of the building that lay in front of the apse — are painted in a muted gray, a melding of the strong crimson light that dominates the left side of the painting and the obsidian blackness that swallows much of the right side. This section of the building is not subject to the pronounced lighting effects that characterize most of the painting. It is a neutral zone, one that nullifies the chromaticity of the artwork and punctuates the conspicuous division between the two sides.

One cannot ignore the clash of light and shadow that permeates the composition. On the left, the columns are foundationally undisturbed, austere, and starkly rendered, and most of the idols in this area of the temple have not yet been destroyed. The religious iconography is unscathed but for one sculpture sustaining injuries in the lower left corner. This sculpture is nearly achromatic and much paler than the other idols, almost as though it had no place in the temple. Its destruction is muted by the intricate details rendered above the scene. Conversely, the right side of the painting is undergoing a voiding process as the composition crumbles before the onlooker. The columns do not erode as they might in a natural setting; rather, their abolishment is instantaneous, facilitated by an explosion whose origin is concealed between them. The observer’s inability to see the source of the temple’s destruction accords with the normal experience of a ruinscape; it is not always something whose genesis can be known, even if we manage to delineate the ways in which it affects those around us. Some parts of the shattered columns have already settled on the ground, while others are only beginning their descent. If the painting is read from left to right, as one would typically read a literary narrative, the destruction of the idols (which is not as evident as the destruction of the temple itself) manifests as temporally unsound.

Similarly, in Desiderio’s The Burning of Sodom, the distortion, amplification, and subdual of light articulate an uneven sense of destruction. The nucleus of the painting — a burning tower — contains its brightest, most saturated element. The tower emits an otherworldly light that is noticeably different from the fires that have razed Sodom. Some of the tower’s wooden beams protrude from its side, as though to announce the building’s imminent disintegration. Yet the base of the tower radiates with an argent hue, and the pinnacle of the building projects sharp beams of light like an aureole, the luminescent cloud that surrounds venerated persons in paintings. The exalted position of the light beams also produces an effect like a crown of incandescence. The tower in the painting is afforded an unusual status due to its discordance with the circumambient elements. It is a sacredlike monument at the zenith of destruction, and its bright light poises the building at the beginning of a swiftly expanding conflagration. This domain of light is distinct from the other scenes of destruction, where a deeper, scarlet-hued fire has flattened the other buildings of Sodom. Whereas the central tower retains much of its architectural integrity, the surrounding structures are practically unrecognizable, and their identities are subsumed by flame.

The painting is crowned by and situated upon blackness. If one observes the base of the tower, they will notice that the structure is hardly altered. However, when one continues to gaze upwards, it becomes clear that the foundation of the tower is not representative of the structure’s condition. Indeed, smoke rolls from the exposed top of the building. The tower produces overwhelming light and stifling blackness, and it is an apotheosis of fire and smoke. In the lower right, Lot’s wife — now a pillar of salt — stands as an anonymous, comparatively minute figure. Like the tower, she too seems to radiate beams of light (although it is likely that these are the flames consuming her, not originating from her). The composition of Lot’s wife faintly echoes that of the tower, although it is obvious which element of the painting takes precedence. Not even the biblical narrative of Lot’s escape seems important. He can be seen at the edge of a dark forest with two angels. The three figures are walking into the forest, a domain of blindness at the literal edge of the painting.

The image and its story suggest that, if Lot and the angels continue moving away from Sodom, the spectator watching Sodom burn will lose sight of the human elements, and all that will remain is the architecture. Lot has turned against the spectacle and he cannot look back. For him, the history of Sodom has reached its conclusion. For Lot’s wife and the painting’s observer, however, Sodom continues to exist. Like pillars of salt, the spectators are frozen at one moment in time, although time continues beyond them. The observer appears to transgress God’s command by watching the burning of Sodom. In actuality, however, the observer shares a similar fate as Lot’s wife. As long as one views this painting, he will be unable to turn away from the scene of Sodom’s decay. The parallel extends to encapsulate the interactions between the ruinscape and the observer who, for some reason, is attached to a scene of devastation. There may be repercussions for treating the ruinscape as something other than what it is, or investing it with aesthetic or sentimental values that are, if not completely absent, disharmonious with a specific historical instance. Lot’s wife looked back and marveled at the wrong time. Who is to say that the beholder of ruins is not within the same juridsdiction as she is?

I believe the function of Desiderio’s paintings are more exhibitory than didactic; the contrast of lightness and darkness, stability and erraticism, volume and nonspatiality, human and architectural intensifies the degree of transition that each painting treats. Desiderio’s aestheticization of ruins moves away from Romanticism without entirely denouncing it. He offers visual hints of what may have been a site of former beauty, but he also shows the speed and extent of violence with which these landscapes may be denatured. Despite the inorganic dissolution of architectural space that is often associated with ruination, Zucker writes, “Definite structural organization and spatial relations, modified as they may be through destruction…still prevail and are still — through the maze of time — perceived as such.”[ref]Ibid., 129[/ref] Zucker believes the grandeur of the original site persists even through demolition and adaptation by future generations. When the observer appraises a ruinscape, then, he may be appreciating the natural or artificial distortion of some forgotten architectural agenda. Still, Zucker himself explained that his three categories were not to serve as comprehensive explanations for the aesthetic of ruins. Some painters, such as Franceso Guardi, suppressed the Romantic imagination in their work, transplanting ruins into the receding environments of playfully rendered scenes. A modern example of the non-Romantic ruinscape appears in a work of literature that is so woven with images of abandonment that it might suffice to call the representation of ruin an “anti-aesthetic” — a deconstruction and critique of preconceived notions of what constitutes a thing’s aesthetic value.

III. Blood Meridian, or the Anti-Aesthetic in the West

In his essay, “Ruins and History”, Andreas Schonle describes ruins as “broken material chards that point, not to an original whole, nor to binding intention, let alone to a transcendant world, but that exist in a random, artificial, and conventional state.”[ref]Andreas Schönle, “Ruins and History: Observations on Russian Approaches to Destruction and Decay” Slavic Review, 65 (2006): 651, JSTOR, 6 October 2013[/ref] For Schonle, ruins lack a unity of form, and they do not indicate purposeful craftsmanship. Ruinscapes are mere fragments that retain none of the gravitas with which they were invested in classical portraiture. Unlike Zucker, who believes that ruinscapes still delineate some likeness of the architect’s vision and uphold their spatial composition, Schonle subscribes to the anti-aestheticism of the ruinscape, “a random telescoping of elements that fails to reveal a unifying artistic will.” He believes that the cultural appropriations of ruins in 20th century film and literature has led to a “re-aestheticization of cataclysm”, and he objects to this romanticization since he believes it divorces the spectator from the tragic dimension of the site. Ruins are nothing if not nesting grounds for forgotten human willpower, and the architectural design is not transformed over time; rather, it disappears. The absolute erasure of the design is ensured even by a partial de-evolution. If the structure does not align with the foundational vision, its existence is nullified and removed from all historical timelines, and Schonle believes this phenomenon should be grieved, not glamorized.

Moreover, ruins demonstrate a rupture in temporal progress, and they become sites of critique, stillframes that urge the viewer to contemplate how a structure could have been allowed to come to this point. Recalling Zucker’s second categorical definition, Naomi Stead goes so far as to suggest that applying one’s own aesthetic of transfiguration onto a ruinscape makes one liable to commit a historical crime. She suggests that there is a schism between the fantastical and historical, and to attempt to locate where these converge is a gross misstep that could permanently damage the historical fabric.[ref]Naomi Stead, “The Value of Ruins: Allegories of Destruction in Benjamin and Speer” Form/Work: An Interdisciplinary Journal of the Built Environment, 6 (2003): 6 October 2013[/ref] Doing so puts us at risk for forgetting the origins of historical structures. One should question why monuments that have undergone ruination may augment the observer’s understanding of the past; that is, what do ruinscapes themselves indicate other than the durable materiality of the site? The danger of using ruins as historical documents lay in the fact that they have often been eclipsed by their emotive potential. Ruins pose a threat to the veracity of the past, and whether they should survive as reliable indications of times gone by is dubious.

Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, or the Evening Redness in the West contextualizes its ruinscapes as sites of perverse sacrosanctity, which are godless, unsentimental, and overhwlemed by nature. They are temporally illogic monuments, and their purposeful obliteration from a historical timeline renders history as a sort of “afterimage” that can only be seen in the present. The nature of the narrative itself is bleak. It is a tale of unremitting violence in the American Southwest, scalping gangs that war with natives and one another in the indeterminate borderlands of America and Mexico. The setting of the story hinges on the unknowable, as the reader is constantly shifting between different, innominate locations. These transitions are often unforeseen and forceful, and many of McCarthy’s characters behave similarly, murdering entire tribes of men, women, and children without forethought. The novel’s plot and characters are exemplars of instability, and this prepares the reader to experience the temporally and structurally volatile ruinscapes.

One of the novel’s recurrent motifs is that of abandoned, communal locations (e.g. churches and villages). McCarthy’s aesthetic does not glorify the scenes he describes, and brief descriptions of former exuberance are offset by more prominent details of natural appropriation and reassignment. Take this passage, for example:

[The kid] woke in the nave of a ruinous church, blinking up at the vaulted ceiling and the tall swagged walls with their faded frescos. The floor of the church was deep in dried guano and the droppings of cattle and sheep. Pigeons flapped through the piers of dusty light and three buzzards hobbled about on the picked bone carcass of some animal dead in the chancel…The buzzards stepped down one by one and trotted off into the sacristy…In the [sacristy] was a wooden table with a few clay pots and along the back wall lay the remains of several bodies, one a child…[ref]Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian, or the Evening Redness in the West (New York: Vintage International, 1985), 26[/ref]

The first point of interest is the protagonist himself, a boy referred to for most of the novel as “the kid”. Only near the end is he ever called a “man”, and this occurs soon before his disappearance from the novel, the nature of which is not specified (the man finds the novel’s antagonist, Judge Holden, in an outhouse; most readers, scholars, and critics have agreed that the man is destroyed, although McCarthy does not reveal how). The kid’s name is never revealed, and there are only fleeting references to his family and home in the first few paragraphs of the book. If this qualifies as knowledge of the kid’s origins, that is acceptable, but over the course of the novel, the kid’s identity is forged anew by the hand of violence. Over time, he becomes an anonymous target of uncontrollable forces, and Judge Holden is probably the most significant entity acting against him. In the passage above, the nameless protagonist awakens in a place of which he has no knowledge. He knows neither how nor why he came to be here. The ruinous church is, foremost, a place of unknowing, initially unrecognizable to the spectator (who, in this instance, happens to be within the building itself). The act of awakening echoes the moment of birth; this is not a rebirth, but an initial one, and the desolate womb eliminates memories that may have been acquired in some previous, unknown life.

The aesthetic presence here is underwhelming, although McCarthy does include information about the “vaulted ceiling and the tall swagged walls”, on which are painted frescos. These paintings, however, are disappearing, which suggests the disappearance of aestheticism from the interior of the church. Aesthetics are not entirely absent — there may still exist vestiges of beauty — but McCarthy positions the protagonist so that he witnesses the process of annulment. The kid is in the middle of a transitioning ruinscape, but the former splendor of the site is bleeding from the wounds of the church. The church is also overrun by wildlife, and McCarthy’s details are sacrilegious. He first describes the ground of the church as overrun with droppings from birds and bats. These beasts have claimed the site long ago, and their vile proof is unavoidable. That cattle and sheep have also come through the church insinuates the deracination of beast and man. Calves and lambs, who should be browsing in distant pasturelands, are here in the desert landscape, within the walls of a place wherein they would normally be slaughtered. McCarthy reverses the slaughter, though, as men kill one another outside the walls of the ruinscape. This is supported by the three vultures that eat a dead animal in the chancel, which is traditionally reserved for the altarplace. Animals avoid the sacrifice here and are even at liberty to satisfy their appetites. They fulfill their gluttonous wants before almost playfully “trotting” into the sacristy where they will probably befoul the sacred vestments that are kept there. The desecrated church divides and reverses the worlds of human and animal, and the ruinscape threatens to undermine traditional modes of identification. Historical truth is a non-factor in a place that can manipulate history and subvert the supposed dominance of man.

The illogic of the ruinous church is marked by the presence of a dead child. McCarthy gives the reader minimal information about him, just as he attributes few details to the protagonist, who could very well be staring at himself — an originless creature who appears without explanation between the tenuously existent church walls. The nature of the child’s death is also unclear, as is that of the kid. This evinces the ruinscape as a site of prognostication, not retrospection. Here, the historical events that have led to ruination cannot be known, but it may project a vision of the future, even if this future will unfold in a debased world order. The child transitions outside of the building, where he sees the following:

The façade of the building bore an array of saints in their niches and they had been shot up by American troops trying their rifles, the figures shorn of ears and noses and darkly mottled with leadmarks oxidized upon the stone. The huge carved and paneled doors hung awap on their hinges and a carved stone Virgin held in her arms a headless child.[ref]Ibid[/ref]

Even more pronounced outside the church is the destruction that has been enacted upon religious imagery. The saints have been disfigured by bellicose American soldiers. This is a reverse transfiguration, a descent into a primal ugliness that distorts their external features. The Americans arranged the rejection of a world guided by saints and God, and the repercussions are clear. However, the church doors are gaping, as though to allow entry to any visitor who so wishes to come. But he who passes into the ruinscape enters a world not like the one from which he came. The god of this church, who lay headless in the Virgin Mother’s arms, is a nullity. The ruinscape is a repository for divine vengeance, although the nature of the divine is equivocal. Is it the God of men or that of animals, the latter of which have monopolized once hallowed grounds? McCarthy’s ruinscape warns the observer that one who is present within may have unwittingly subjected himself to a universal system entirely unknown to him. Even if the church is remotely beautiful, that no longer matters. What the spectator should instead focus on is his own temporal endangerment.

This church is the first ruinscape that McCarthy treats in his novel. Not long afterwards, the Glanton gang that the kid rides with “passed through a village then and now in ruins.”[ref]Ibid., 50[/ref] The gang camps in a mud church, burning the fallen timbers of the roof for fire “while owls cried from the arches in the dark.” Again, McCarthy does not assign an origin tale to the church, which seems always to have been a ruin. If this ruin is a historical document, it is a defective one since it presents no reliable information about the past. The gang encounters yet another church after camping here, and the effect is one of redundancy. These landscapes are defined by their many ruins, most of which served a similar purpose. The number of disused churches in Blood Meridian may be many, but they might as well be one. There is a horrific monotous element to McCarthy’s ruinscape that suggests an inability to discern a thing’s individual characteristics. The kid and the dead child. The first church, the second church, the third church. Here is a description of the kid’s experience inside the third chapel:

Long buttresses of light fell from the high windows in the western wall. There were no pews in the church and the stone floor was heaped with the scalped and naked and partly eaten bodies of some forty souls who’d barricaded themselves in this house of God against the heathen. The savages had hacked holes in the roof and shot them down from above and the floor was littered with arrowshafts…The altars had been hauled down and the tabernacle looted and the great sleeping God of the Mexicans routed from his golden cup. The primitive painted saints in their frames hung cocked on the walls as if an earthquake had visited and a dead Christ in a glass bier lay broken in the chancel floor. The murdered lay in a great pool of their communal blood.[ref]Ibid., 60[/ref]

This church shares much in common with the first, although it is distinguished by the number of human corpses within its walls. The passage begins with a pleasant description of light descending, but then shifts to a language of absence. There are no pews, for instance. Worshippers have no place in this malformed churchhouse. Instead, the space is occupied by forty corpses. The biblical significance of the number is obviously not lost on McCarthy. In the Old Testament, the number forty recurred as a numerical symbol of God’s tests for man. Christ’s temptation endured for forty days. Egypt was to be laid desolate for forty years. Forty strikes was the maxiumum whipping penalty. Each of the deceased has failed to survive divine trial, and their defeat is magnified and mocked by their nudeness. They are scalped and partially eaten, so not even their nakedness makes them recognizable. The individual is not distinguished in a “pool of their communal blood”, they who had locked themselves in this place, the narrator tells us. Although the narrator does not usually present such information, this knowledge accentuates the tragic element of the slaughter. The reader is told that these corpses were once living people. It is not as though the dead have always been dead, as is suggested by the first church. Although their deaths are irreversible, they are explicable. This is as bright a light as McCarthy is willing to give. It is as though he is saying, “This ruinscape — this particular church — has an origin, which can be known.”

The arrow-covered ground resembles a post-skirmish battlefield, another supplantation of a familiar domain. Whereas the first church reversed the worlds of man and animal, this temple reverses the contemplative and god-fearing universe with one of pervasive war. Battle has found its way into the temple of God, and no sacred object is immune to its effects. Altars and a tabernacle are mistreated and removed. Effigies of saints have been disturbed, as though by a vague supernatural phenomenon, and a “dead Christ” lay in broken glass around the altar. While the vultures enjoyed their feast in the other church, the messiah here has not risen. These ruinscapes are highly irreligious, and the extent of their destruction is only clear when one has experienced many of them.

As the novel progresses, the ruinscapes become increasingly less beautified. Near the middle of the story, in the proverbial heart of darkness, the gang camps “in the ruins of an older culture deep in the stone mountains, a small valley with a clear run of water and good grass.”[ref]Ibid., 139[/ref] Once more, McCarthy’s offering of a few aesthetically-pleasing details is a sardonic gesture that prepares the reader to witness the true nature of the ruinscape. Broken pottery shards and other old artifacts memorialize the people who had once lived here. Judge Holden, however, inherits the role of the anti-historian. McCarthy writes:

The judge walked among the ruins at dusk, the old rooms still black with woodsmoke, old flints and broken pottery among the ashes…He roamed through the ruinous kivas picking up small artifacts and he sat upon a high wall and sketched in his book until the light faded…A Tennessean named Webster had been watching him and he asked the judge what he aimed to do with those notes and sketches and the judge smiled and said that it was his intention to expunge them from the memory of man…Webster regarded him with one eye asquint and he said: Well you’ve been a draftsman somewhere and them pictures is like enough the things themselves. But no man can put all the world in a book. No more than everything drawed in a book is so.[ref]Ibid., 140[/ref]

The judge acts with a singular purpose. Throughout the book, he is a quasi-supernatural figure who is physically imposing and bizarre (i.e. completely pale and hairless), philosophically and scientifically well-versed, and stunningly violent. He is a mythopoetic invention who McCarthy transplants into a similarly fabular world. The judge stalks the ruinscape during the night, when it is difficult to see, and the rooms of an expired people are “still black” from some bygone era. The near-blindness of the environment portends the judge’s agenda of historical cancellation. As the judge continues to maneuver through the households, he pauses to sketch small artifacts. Initially, he appears to be a working recorder, a draftsman of a ruinscape whose history has not yet been articulated. His drawings have the authenticity of a professional, but he intends to eradicate that which he draws from the historical consciousness of man.

By drawing the artifacts, the judge effectively buries what is already dead. It is not enough that this ruinscape is not what it used to be. The judge is compelled to efface the ruined world by keeping it sequestered in his journal. His sketches are facsimiles of the forms they replicate, and drawing is for him an act of mythopoesis. The mythology that he engenders is one of the spectator’s blindness. In this way, the judge imitates the ruinsite as an object of false aestheticism. He creates an accurate depiction of a historical thing, but really what one sees in his sketchbook is not, and can never be, the thing depicted. In the same way, the purported aestheticism of a ruinscape seems to announce a historical provenance, but this may only illustrate a recreation of the truth, which is no longer knowable. The memory of the structure has been extracted and discarded, and the Judge characterizes the unnamable force that accomplishes that.

The mythological conceit of the Glanton gang is confirmed in a later section of the novel, which frames the Americans as terrorsome and ethereal migrants through a town on the verge of ruination. The author writes:

The Americans entered the town of Carrizal…their horses festooned with the reeking scalps of the Tiguas. The town had fallen almost to ruin. Many of the houses stood empty and the presidio was collapsing back into the earth out of which it had been raised and the inhabitants seemed themselves made vacant by old terrors…Those riders seemed journeyed from a legendary world and they left behind a strange tainture like an afterimage on the eye and the air they disturbed was altered and electric.[ref]Ibid., 174–175[/ref]

The scalpers ride with their horrific war spoils like a coterie of unvirtuous soldiers. They traverse through a town that is in a state of transition, and the setting appears to slowly descend into the earth that gave it rise. As the Americans move forward on their horses, the ruination of the village is accentuated. Their voyage correlates with the rapid decline of the southwestern landscape, and their presence is bemoaned because the villagers seem to recognize them. The Americans are “old terrors”, as though long ago they had made this same trek. Their visitation confirms the repetitiveness of the “aesthetic” ruinscape.The southwest is a domain of architectural and existential echoes (e.g. the repetitious churches, the sensation that these riders have been here before), and this cyclicity induces dread. The mythical riders have come directly from a “legendary world”, but the townspeople may not actually be witnessing the present. Indeed, the riders leave behind an uncleanliness “like an afterimage on the eye.” It is possible that these inhabitants are frightened by something that is already gone. The harbingers of ruination proceed unnoticed into the future, while those in the midst of ruination struggle to discern the source of their frustration. This struggle, McCarthy suggests, is not an advantageous enterprise. The overwhelming force of the Judge defies the aesthetically-enjoyable or nostalgic ruinscape by purging it from existence. If there ever was such a thing, it is now permanently absent. For as long as the Judge lives — and one surmises that he persists well beyond the pages of the novel — the ruinscape will be unable to convey any historical truth, and the memory of former beauty will be extinguished.

IV. Home

On an episode of 60 Minutes entitled “Detroit on the Edge”, Bob Simon interviews a local firefighter about his department’s financial concerns, which has sometimes prevented the department from responding successfully to a basic fire. The firefighter says, “I believe that people in the city have lived with it this way for so long that maybe they don’t understand that this isn’t how it’s supposed to be.”[ref]Bob Simon, “Detroit on the Edge” 60 Minutes, 13 October 2013[/ref] This statement probably holds true to some degree for many Detroiters, myself included. It is tempting to cite the 1967 Detroit riot as the beginning of the city’s modern history. Detroit’s story, people seem to believe, is of a pheonix that forgot to rise from the dimming fires. The riots permanently scarred many residential and commercial areas in the city, and some of the effects are still evident. Ironically, the site at which the riot began has since been converted into an attractive public park. Certainly the riots were a significant turning point, a critical rupture that was the climax of accumulating racial and economic tensions. Since the mid-20th century, Detroit has lost more than half of its population, and has become well-known for its pecuniary and political misfortunes.

Author Mark Binelli proposed that the essential question of Detroit is one of aesthetics, which, for the city, has become synonymous with “ruin porn”, an unflattering phrase used to describe the immoderate fascination with urban architectural decline.[ref]Mark Binelli, “How Detroit Became the World Capital of Staring at Abandoned Old Buildings,” The New York Times, Nov. 9, 2012[/ref] Binelli believes the vacated industrial yards and burnt-out homes offer photographic souvenirs for tourists and reporters from around the world. These urban ruinscapes have sometimes been repurposed for recreation or artistic burgenoning. In service of her art, one woman took nude photographs of herself in some of Detroit’s most exposed structures. During the winter, some people play ice hockey on the frozen floors of empty buildings. The most architecturally impressive Detroit ruinscape is probably Michigan Central Station (pictured above, on the right), an 18-story Beaux Arts complex with terrazzo floors and high ceilings. Having been closed since 1988, the former Amtrak station has come to symbolize the extent of Detroit’s structural degradation.

During a public talk that Binelli attended, one Detroit citizen noted that “devotees of ruined buildings should be aware of the ways in which the objects of their affection left ‘retinal scars’ on the children of Detroit, contributing to a ‘significant part of the psychological trauma’ inflicted on them on a daily basis.’” This observation is critical, as it begs the observer of the ruinscape to contemplate the ethical consequences of aestheticizing ruination. For Detroit specifically, this citizen believed, people should discontinue their publicized admiration for these structures. To aestheticize the urban ruinscape as anything other than a somber testament of decrepitude is to neglect the very people that live among these sites. Even if the worn architecture satisfies one’s aesthetic preoccupation, treating it as a museum relegates Detroit’s struggling citizens to a negligible position. The people become ornaments for the more interesting architectural features of the place, and Detroit loses its status as a city of human beings. It becomes a resting ground of the Packard Plant, the absent Chinatown, the hardstruck projects of Cass Corridor. It is not a place where some people still live, but a place where, at one time, many people had lived. The language of absence reappears in discussions about Detroit, and this has unfortunate consequences for those who would attempt to reconstruct an image of the city. This may also harm the city’s inhabitants, especially its predominant African-American population. If a child in a low-income household is told for most of his youth that his home is a kind of “no man’s land” that everyone is afraid to touch, the likelihood that he will contest this viewpoint is unpromising. If there are more images on Google of empty, “post-apocalyptic” fields than there are of happy Detroiters, how is a child to know that the world cares for his fate? I do not know. If all ethical avenues are closed, aestheticizing urban ruins may lead one to acquiese to his own decline.

The photographs of Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre are the most well-known examples of the aestheticized Detroit ruinscape. A description on their website reads as follows: “The state of ruin is essentially a temporary situation that happens at some point, the volatile result of change of era and the fall of empires.” Their explanation of the ruin is an unfortunate simplification. That a ruined state is “temporary” may be moot. One has only to look at the Old Summer Palace, Tsarskoe Selo, or the Coliseum to find the error of this argument. The artists compare the abandoned buildings of Detroit to the monuments of Egypt, Rome, and Athens, saying that they “have become a natural component of the landscape.” They conflate the slowly orchestrated devolution of the city’s buildings with an event that is entirely natural, like an overgrowth of weeds. In their pictures, the ruinscape is always the subject. There is no sign of human life in the present or future, and their role in the past is only implied by elaborate graffiti tags, windows set ajar, apartments that look as though their occupants have just left. In the famous image of Michigan Central Station, the building occupies the entire frame and extends beyond it. There is no doubting the dehumanizing immensity of the place. Observing the building is discomforting, like peering into the casket of a beloved one. One knows it was once vital, and it had brought them joy. Now, however, the loss is accentuated by this former happiness, and the absence will remain.

I could not ignore the image of a dentist’s office on the 18th floor of the David Broderick Tower. The office is a tiny, suffocating space that is slightly larger than an average closet. The broad window affords a look outside. There is a dentist’s chair with some rather ominous implements beside it, and patches of the wall are shorn of their original paint. The office is not simply abandoned; it looks as though there could have been a human presence a few moments before. One wonders what events transpired that caused the office to be left in its current state. If there is a pleasant aesthetic here, it is not obvious. Similarly, the interior of the United Artist Theater, an example of Spanish Gothic architecture, is like something from the sketchbook of a Baroque painter. The roof is as intricately designed as that of a mosque, and hung from it are stalacite-like projections. The golden fabric that hangs from the proscenium reminded me of great organ pipes appropriate for only the largest cathedrals. Spirelike projections around the stage look weighted with spikes, barbs, pines, and other medieval weaponry. The light from outside falls on certain spots, as though the actors are about to debut. But, of course, they will not. Then there is the William Livingston House, which is almost as perplexing as the home Gordon Matta-Clark used for his New Jersey project. The house literally leans to the side, bracing itself for collapse. It is torn between inaction and self-cancellation. The windows are boarded, and some of the bricks have eroded. If you didn’t know any better, you might think to push it over with your own hands.

John Patrick Leary, writing about Marchand and Meffre, says that their artwork, rather than extolling the city’s beauty, exemplifies nothing so clearly as it does the city’s devastation. The “meta-irony” of these pictures is that they themselves are resigned to historical oblivion. Because these are merely pictures that don’t offer the spectator the interactiveness that a ruinscape demands, they are ultimately pictures “of nothing and no place in particular.”[ref]John Patrick Leary, “Detroitism,” Guernica: A Magazine of Art and Politics, Jan. 5, 2011[/ref] These images succeed only as minor plot points in a massive narrative that we cannot quite piece together.

I could go on about their photographs. They document a frozen clock (which immediately summons Dali’s The Persistence of Memory) in an abandoned school, a Methodist church with destroyed pews (above which, on a wooden railing, is a scriptural engraving that reads, “And You Will Say God Did It”), and classrooms with upturned desks and chalk still on the walls from an old lesson. I suspect that Marchand and Meffre’s work discredits their own goal of capturing the splendor of ruination. Yes, the sheer space and volume of some of the buildings, and the violent contrasts between the interior and exterior worlds are striking, but I am not convinced that this reaction always carries positive connotations. I have walked by many of these buildings, and frequently I toyed with the idea of walking into one of them. But I never did, and I think this is because the emphatic absence of each location is so unfamilar to me that the experience would be more harrowing than enjoyable. These had been sites of human interaction and sociability, but this original architectural function has long since gone.

In the documentary Detropia, Crystal Starr, one of the people that the filmmakers follow, walks through the halls of an old building, contemplating history itself. “I’m picturing this place clean,” Starr says, “and there being, you know, people walking around and shit happening.” Like many Detroiters, she is only able to imagine her city as it may have been, and she attempts to recreate its history within the walls of a ruinscape. “I feel like I was here just a little while back,” she continues. “Or, I’m older than I really am and I just have this, like, young body and spirit and mind but I have a memory of this place when it was [populated].”[ref]Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady, Detropia, Documentary, directed by Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady (2012; New York: Loki Films/ITVS)[/ref] The familiar trope of the ruinscape’s atemporality affects Crystal inside the building. She feels some recollection of an uncertain past that was filled with people, and her body and mind are placed on separate temporal continuums. In effect, she is split into two personae who perceive time differently. The ruinscape confuses the spectator’s understanding of time, raising more questions than it answers, and thus fails as both a historical document and aesthetically-calming construction.

This discussion does not underscore the great complexity of the modern Detroit story. Beyond the ruinscapes, there are very real narratives of urban redevelopment and farming, neighborhood reinvention, and the positive artistry and activism of residents both native and foreign. I believe that, for many people, Detroit stands as a warning of urban and capitalistic decay. Perhaps in no other American city is there a more defined sense of ongoing finality or, at least, temporal havoc. The confusion of Detroit’s history and its increasingly uncertain tomorrow allows one to view it as a paradigm of an unwelcomed future condition. People can travel from any part of the country (or the world), visit one of the local businesses, and say, “This is the conclusion of Detroit’s history, if there ever was one, and now we have to make sure it doesn’t happen to anyone else.”

That is unacceptable. If the urban ruinscape is one measurement of a place’s decline, there is an implicit responsbility to address the socio-political and economic circumstances that have alllowed this state to exist. The importance of the ruinscape lay in its proclivity to captivate the spectator’s emotions. On the one hand, these sentiments can be used unproductively by enamoring the observer with the ruinscape’s aesthetics. It may be easier to argue for the aesthetics of a site that people no longer inhabit. Now that the group of people who once used the location for some particular purpose have gone, the observer is at ease to romanticize the ruinsite by virtue of its vacancy. Because these monuments no longer interact with the world of man, the viewer is temporally and emotionally distant from the sensation of melancholia that loss naturally entails. Each ruinscape engages the spectator on a different level, of course, but many have in common an absence of human life. Detroit, on the other hand, and many cities like it, are still peopled. To aestheticize ruinscapes as though they are markers of a non-existent culture is harmful to a city’s reinvigorative efforts. I do not know how much time will pass before Detroit restores a respectable image. However, the mentality of post-apocalyptic tourism does nothing to assist. Instead, we must begin to incorporate the monumentalism of dilapidated urban architecture into conversations about a city’s cosmetic rehabilitation. If an attractive physical appearance is a prerequisite for internal contentment, people must be responsible for the language they use to describe a location. It would be foolish to suggest that all Detroit needs is an artificial surgery. However, it is the spirit of the people that will enact transformation. If the spirit can be mended by de-aestheticizing the city’s scars, then may we all use gentler words.